Back To Basics Series

CSS #1

Web page structure

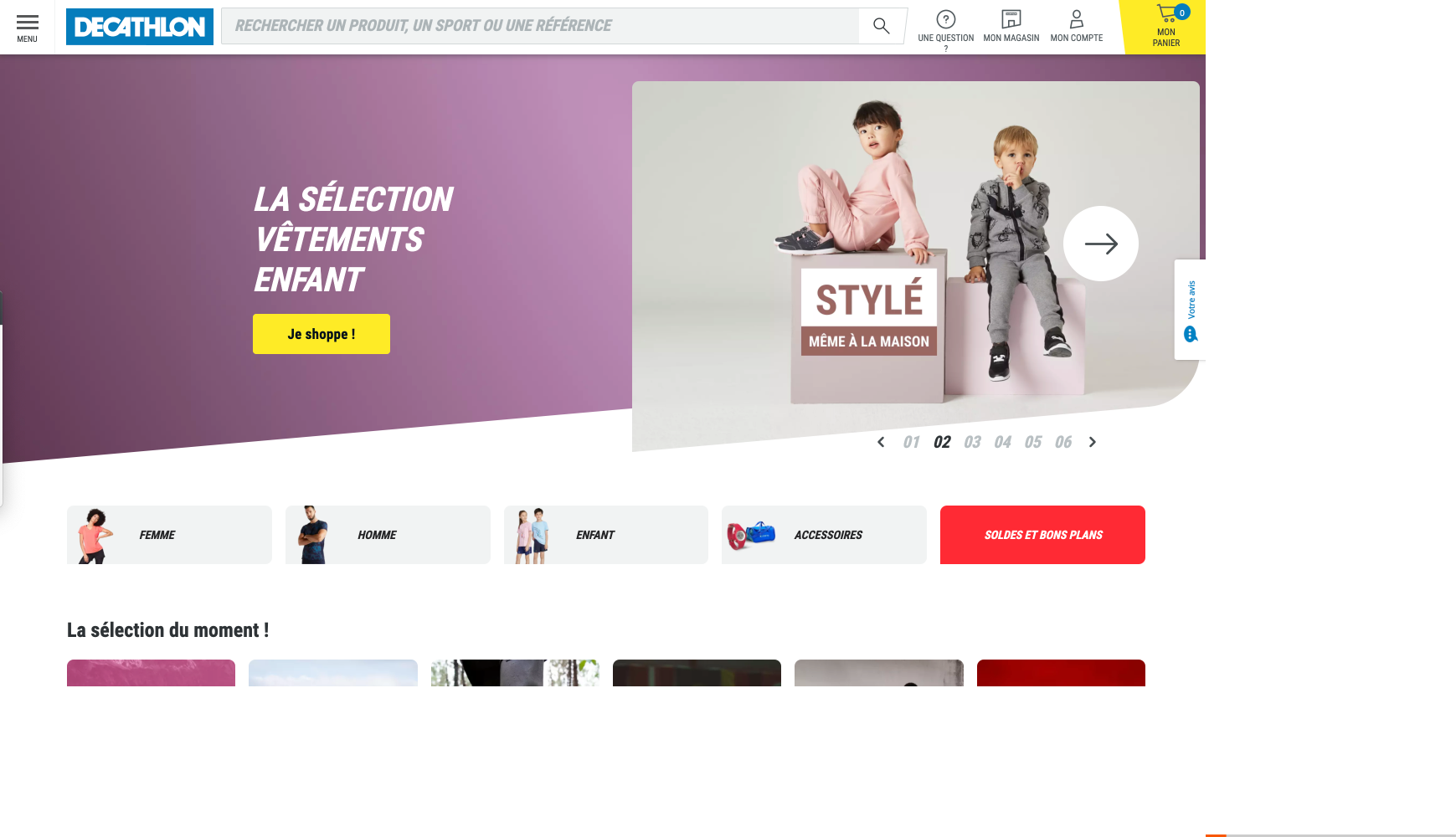

Example Decathlon.fr without CSS

Web page structure

Example Decathlon.fr with CSS

The CSS Story

At the beginning of the web, css didn't exist.

HTML was born in 1991, and CSS in 1996.

At this time,

available styles were really limited.

It was possible to use dedicated tags styles, through, like :

<font color="#aab1c3">text</font>Allowing to define text color.

The CSS Story

As people wanted to have more complex displays, the web

became a mix between styles and contents making it

really difficult to understand.

This is when CSS was created to split styles and contents and make it clean.

Cascading and inheritance

As the name says (Cascading Style Sheet),

a CSS is a sheet listing style rules

applied in cascade to HTML elements.

It means that some styles are directly applied to an element and others

are applied to children by inheritance.

It is specially relevant for font sizes, text colors, line height ...

Cascading and inheritance

The main benefit is that we don't have to apply style rules

to every element, you only have to apply generic styles

on the top elements of the HTML structure

This is why we define generic styles on top elements like

<html> and/or <body>

Cascading and inheritance

Then every styles of an element can be overridden or completed by more specific ones breaking inheritance.

Browsers compatibility

CSS evolution is ruled by W3C (international consortium)

(W3C for World Wide Web Consortium),

where every rule and CSS version

is made official

CSS is currently in version 3, released in 2005.

Browsers compatibility

When a feature is not official,

it stays as a draft for a while,

but can be used and adopted

in many different ways by browsers

(prefixes, special displays and behaviours, ...).

It is only when it is mature and used enough

that it is made official.

Browsers compatibility

For example, Grid Layout

was only made official after many years

of discussions and various validations.

During this time it evolved and was used

by some developers who couldn't wait

helping the feature to be better but

costing many updates

Browsers compatibility

As CSS is constantly evolving

it is important to know which rules to use

depending on browers compatibility

If you need to check browser compatibilty

visit www.caniuse.com

Anatomy of a CSS rule

A CSS rule is composed of a selector,

used for targeting one or many elements

on which you want to apply styles

selector {

}

Anatomy of a CSS rule

...containing one or multiple declarations ...

selector {

declaration;

}

Anatomy of a CSS rule

Declarations themselves are composed of a a property/value couple

selector {

property: value;

}

Which gives us :

p {

color: red;

}

Some examples

body {

font-size: 16px;

font-family: "Times", serif;

}

Some examples

body {

font-size: 16px;

font-family: "Times", serif;

}

.main-section {

position: relative;

padding: 1rem 0;

border-top: 1px solid #ccc;

}

Some examples

body {

font-size: 16px;

font-family: "Times", serif;

}

.main-section {

position: relative;

padding: 1rem 0;

border-top: 1px solid #ccc;

}

.main-section > p {

/* external margin of 16px top and bottom, and center horizontally */

margin: 1rem auto;

width: 600px;

font-style: italic;

font-size: 1.25rem; /* 20px */

}

Some examples

body {

font-size: 16px;

font-family: "Times", serif;

}

.main-section {

position: relative;

padding: 1rem 0;

border-top: 1px solid #ccc;

}

.main-section > p {

/* external margin of 16px top and bottom, and center horizontally */

margin: 1rem auto;

width: 600px;

font-style: italic;

font-size: 1.25rem; /* 20px */

}

/* only first letter of every paragraph in main-section */

.main-section > p::first-letter {

text-transform: uppercase;

font-size: 3em; /* 3 x 20px = 60px */

}

Units and values

Some properties expect values with

absolute or relative units.

Absolute units

The most famous : px (pixels).

As its name suggests,

this unit allow us to apply fixed values in pixels.

For accessibility and responsive reasons,

this unit must be used with caution,

and often replaced by others, more responsive .

Relative units

% : percentage

As obvious as it seems,

you always need to know on what it is based

and on what property you should apply it.

Relative units

vw and vh

For viewport width and viewport height.

1 unit is 1% of the viewport

(visible area of the web page).

Relative units

em

For the (font-size)

applied to a parent,

or element itself (as seen previously in cascading).

Ex : for an element that has a 12px font-size ,

a child element with a 2em font-size will be 24px.

Relative units

rem (root em)

It is the font-size of the “root” element,

usually applied on <html> or <body>.

Ex : if a web page has global font-size of 16px,

a child element with font-size of 2.5rem will be 40px.

Other units

There are many more, some are a bit exotic, like :

ex, ch, lh, vmin, vmax,

or even pt (point) and cm, for printing purposes

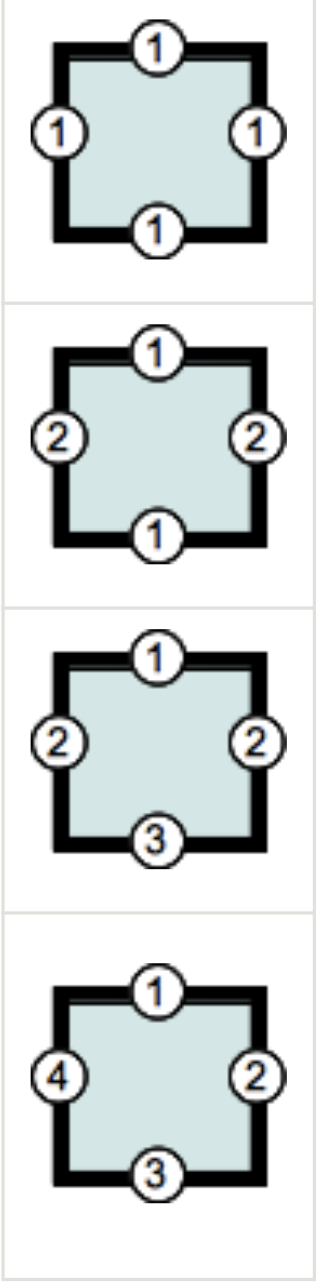

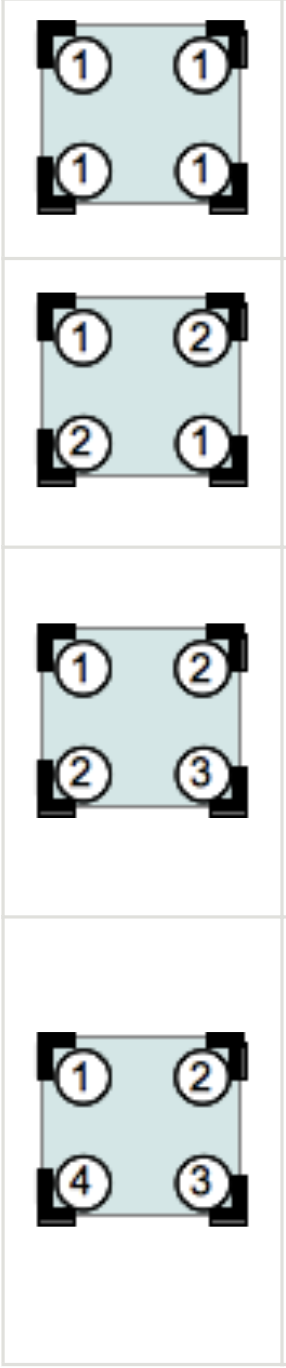

Short-hand properties

Some properties

such as font, padding, margin, background,

can be shortened

Short-hand properties

For example : To add margin to an element, the following...

.element {

margin-top: 1rem;

margin-right: 0;

margin-bottom: 1rem;

margin-left: 0;

}

Short-hand properties

...can be shortened like this :

.element {

/* following the clock rule top > right > bottom > left */

margin: 1rem 0 1rem 0;

}

Short-hand properties

Or also :

.element {

/* top > right/left > bottom */

margin: 1rem 0 1rem;

}

Short-hand properties

Or also :

.element {

/* top/bottom > right/left */

margin: 1rem 0;

}

Short-hand properties

Or even, for a global margin :

.element {

margin: 1rem;

}

Short-hand properties

An other example with property font

{

font-style: italic;

font-weight: bold;

font-size: 1.2em;

line-height: 1.5;

font-family: Arial, sans-serif;

}

Short-hand properties

can be shortened like this :

{

font: italic bold 1.2em/1.5 Arial, sans-serif;

}

Short-hand properties

margin/padding

border-radius

CSS Selectors

All of this is very nice but would be totally useless

if we did not have the selectors, allowing us to target elements which will receive the styles.

CSS Selectors

Universal Selector

Target every HTML elements

* {

color: black;

}

CSS Selectors

Selector of HTML tag

Target every HTML elements of type <p>

p {

color: black;

}

CSS Selectors

Selectors of class

Target every HTML elements

that has the matching CSS class :

.my-class {

color: black;

}

CSS Selectors

Selector of ID

Target the (must-be) unique element with a matching attribute id

Difference between id and class attribute: The only difference between them is that “id” is unique in a page and can only apply to at most one element, while “class” selector can apply to multiple elements.

#id-unique {

color: black;

}

CSS Selectors

Selector of attributes

Target elements with attributes that have

a specific value :

a[target="_blank"] {

color: black;

}

CSS Selectors

Selector of attributes

Other example that targets elements with specified attribute,

even if it does not have a defined value

div[style] {

color: black;

}

Complex CSS selectors

Combined selector

Target elements with all indicated classes

.my-class-1.my-class-2 {

color: black;

}

Complex CSS selectors

Multiple selector

Target elements that match one of the selector

.my-class-1, .my-class-2, quote, a[target="_blank"] {

color: black;

}

Complex CSS selectors

Descendence selector

Target specific children

section p {

color: black;

}

Complex CSS selectors

Selector of direct child

Target direct children elements of specific type

section > p {

color: black;

}

Complex CSS selectors

Selector of direct adjacency

Target elements directly following other elements

// every paragraph following another one

p + p {

color: black;

}

Complex CSS selectors

Selector of indirect adjacency

Target elements indirectly following other elements

// every paragraph following indirectly another one

p ~ p {

color: black;

}

Complex CSS selectors

There are many more,

and it's also possible to combine them.

Pseudo classes

A pseudo class is a key word that can be added to a selector to define a specific state

that elements must have to be targeted

They are defined with “:” (colon).

Examples :

a:hover {}

a:active {}

a:focus {}

a:visited {}

...

Pseudo elements

A pseudo-element is a key word that can be added to a selector to define a display of specific parts of an element.

They are defined with “::” (double colon).

Examples :

a::after {}

a::before {}

input::placeholder {}

...

Good to know, pseudo elements can also be used with “:” because a few years ago, they were not considered different than pseudo classes

Pseudo elements

Some quotes

, he says, are better than none

Pseudo elements

Some quotes

, he says, are better than none

q::before {

content: "«";

color: blue;

}

q::after {

content: "»";

color: red;

}

Pseudo elements

Some quotes

, he says, are better than none

q::before {

content: "«";

color: blue;

}

q::after {

content: "»";

color: red;

}

Some quotes, he says,

are better than none

Selector priorities

Previous note :

Styles applied directly on HTML tags

through style attribute always have priority over CSS.

After we say this : selectors do have priorities.

Selector priorities

At equal priority of selector,

a CSS statement will overrule another one declared before :

p { color: blue; }

p { color: red; }

// red will overrule blue

Selector priorities

But there is a priority rule calculated

upon the nature of the selector and what it combines :

- Level 1 : selector of type and pseudo-element

(p, div, ::before, etc) - Level 2 : selector of class (

.my-class) - Level 3 : selector of ID (

#my-id)

Selector priorities

For example, for a paragraph

...

Blue will keep priority over red :

.paragraph { color: blue; }

p { color: red; }

Selector priorities

Note: careful with overbidding selectors!

Avoid as much as possible selectors

too long or too complex/specific :

main#main-section div.scrollable > div > h2 > ul > li + li { ... }

and use selectors as generic as possible

that you can overrule more easily.

Exception handling with !important

In last resort, it is possible to add

!important to the declaration's value:

p { color: red !important; }

That will take absolute priority

on any selector specification.

Exception handling with !important

It also takes priority on styles directly applied to an HTML element.

In the following example, red will be applied.

...

p {color: red !important;}

Exception handling with !important

If two declarations with !important are in conflict,

priority will be applied in the same manner as any equally specific declarations.

It means that at equal selector weight,

it's the order that will prevail (the last one wins !) :

p {color: blue !important;}

p {color: red !important;}

Otherwise, the most specific selector takes the lead :

p.blue {color: blue !important;}

p {color: red !important;}

Exception handling with !important

Considered as a bad practice

or at least a last resort solution,

it can be useful in one use case :

If styles are applied directly to HTML tags, with Javascript,

and no CSS specification is enough.

Display

The attribute display, applied by default

according to the nature of the element can be updated

Most common values are :

-

inline:

applied to “inline” elements, such as tags to format text (strong,em,span, etc) -

block:

applied by default on elements like paragraph (p), generic boxes (div), or lists (ul,li), etc -

inline-block:

applied by default on tags likeimg,input,button

Display

There are many more values

Most of the time, they are linked to elements types

like table, table-cell, list-item, etc.

Since the release of flexbox, a,d grid layout,

(explained in CSS#2)

this list grew with some values like :

flex, inline-flex, grid, inline-grid, etc...

Native styles of browsers

To have a basic render of a web page

when no CSS is applied, browsers apply

basic styles.

Based upon the nature of an element

(<p>, <a>, <ul>, <strong>, ...),

a specific display can be applied

(block, inline, among others),

and also basic colors, borders, backgrounds, underlines, ...

Native styles of browsers

Example Decathlon.fr without CSS

Native styles of browsers

To get rid of these default native styles, there is the appearance property, deleting these styles

You can use it but keep in mind that it was not

made official yet and compatibility is not always right

Caniuse

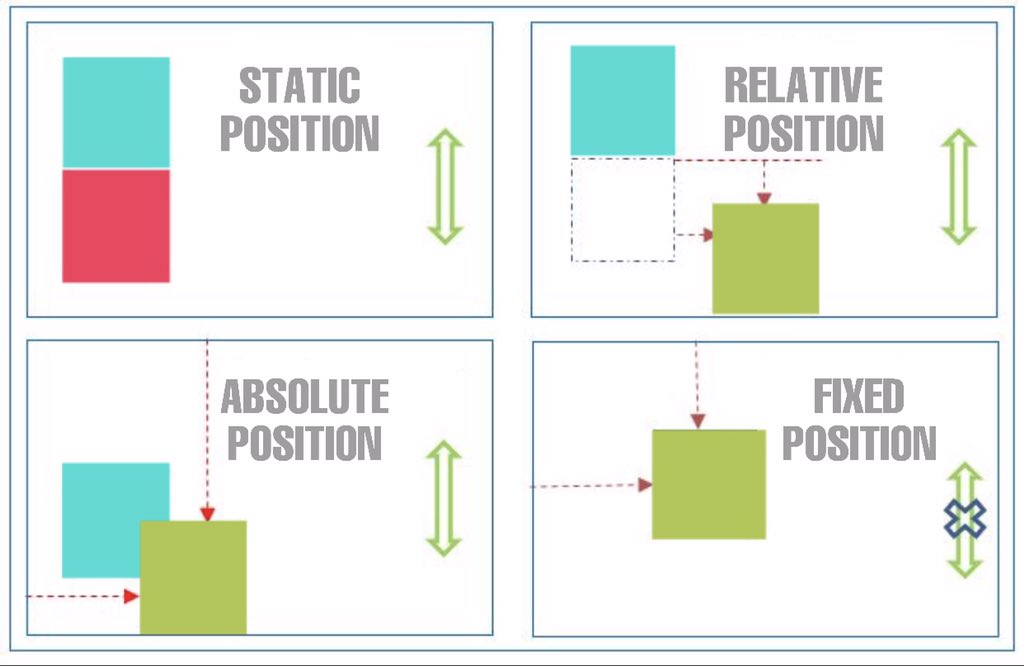

Positions

By default, any element is in “static” position :

position: static.

An element become “positioned” as soon as the property

position is specified (by a value different than static).

As soon as it is positioned, it is possible to move the element by moving properties :

left, top, right, and bottom.

Positions

Explanations of position values

relative:

element is positioned relatively comparing to its initial position. It appears moved on the screen, but it doesn't impact on other elements next to him.

Its initial position will leave an empty spot if you move it.

Positions

Explanations of position values

absolute:

Unlike it may seems, absolute value allows us to position an element relatively to his closest parent positioned.

If no parent element is positioned, positioning will be based on the document.

Element stays dependant to scroll

Positions

Explanations of position values

fixed:

An element infixedposition will be fixed regarding the viewport (visible part of the screen), it is not dependant to scroll whether it has positioned parents or not.

Positions

Explanations of position values

sticky:

The most recent so less compatible one (Caniuse), positionstickymakes an element depending on scroll, giving the impression that the element "follows the user" :

The element follows scroll as a static element, but become fixed when it reaches the limit of the viewport.

Positions

Note : positioning can be source of overlaps.

The z-index property allows to handle

levels of overlap for each element,

to makes them go "higher" or "lower"

A higher value will make an element go up.

If two elements with no z-index or same level are overlapping, it is the last one in the document that will appear on top.

Positions